cuculoris, a time machine for shadows - (2019)

Western Front

May 31 – Jul 5, 2019

Through the process of working I hesitate to say this began with light, as invoking “light” alongside “beginnings” feels so biblical and there’s not much about Nicole Kelly Westman’s work that I’d classify as biblical. That said, it did begin with light—specifically, dappled sunlight in the late summer afternoon. We were talking in a second floor apartment and the warm late summer/early fall September light was streaming in through the large west facing windows. She was sharing with me some of her recent work in the studio that was focused on dappled light, that soft shadowed light that filters through foliage. We talked about how, during the solar eclipse that summer, a miniature projection of the eclipse was projected onto the ground through the leaves. There’s something about dappled light, the way it can mark place and time. Light is such a temporal, slippery substance. Is light even a substance?

Westman had been looking for ways to mark this: the dappled light, the hues of sunsets, the warm glow of an afternoon. Film and photography provided one avenue. Westman had been pointing cameras at patterns of dappled light that she observed on walls, curtains, and sidewalks. Using Super 8 film, the temporality of light was captured, and the pronounced grain and vivid colors of the Ektachrome stock heightened the dramatic effect of the shadows. A film could collect all of these moments—from the mornings and the evenings, the harsh cold light of winter and the warm summer sun—and string them together in a cavalcade of reflections and refractions.

Where motion picture film captured color and movement, it lacked the physical, albeit ethereal presence that characterizes this kind of light. To recreate that physicality, Westman constructed cuculorises. A cuculoris, as she explained to me, is a flat sheet of material—often cut from wood or stiff cardboard—that is placed in front of a light to cast a shadow pattern. A cuculoris is similar to, but should not be confused with a gobo (a pattern cut in metal and placed in between the lamp and focusing lens of a theatrical light). While a gobo casts a very hard lined shadow, a cuculoris generally casts a softer edged pattern of light and shadow. It’s origins date back to cinema in the 1920s when a cinematographer needed to tone down the hot spots from lighting on white clothing or fabrics in a scene. The uneven and random shadow patterns were meant to more closely approximate natural light in the studio environment full of bright artificial lighting.

Natural as the effect may be, a cuculoris remains an artificial lighting instrument. Though used to mitigate the harsh, direct glare of a 12,000 watt film studio lamp, its implementation still manifests as a make-believe shadow. It is but another apparatus of illusion used to help lend some sense of the real in film and photography. This interplay between the real and the artificial, the represented and recreated, the corporeal and the intangible, is at the core of Westman’s work in cuculoris, a time machine for shadows.

As the starting point for the exhibition (well, not the first thing you encounter, but the first thing

Westman and I determined as the foundation for the show), Westman designed a pair of cuculorises to fit over the east facing windows in the gallery wall. For many years, those windows weren’t even visible in the gallery. Original to the 1922 building, the windows were covered up in the mid-1980s, some years after the transition of this room from a social gathering space to the more conventional white cube format it still maintains today. In 2011, Sophie Bélair Clément learned of the walled in windows and requested that one be uncovered for her eponymous exhibition here. After which, the newly exposed window along with its sill and moulding (recreated to match other windows in the building), remained a part of the galleries architecture. Bélair Clément’s intervention only excavated one of a pair of adjoining windows though, the window on the right remaining behind drywall until it was pointed out to Westman in advance of this show.

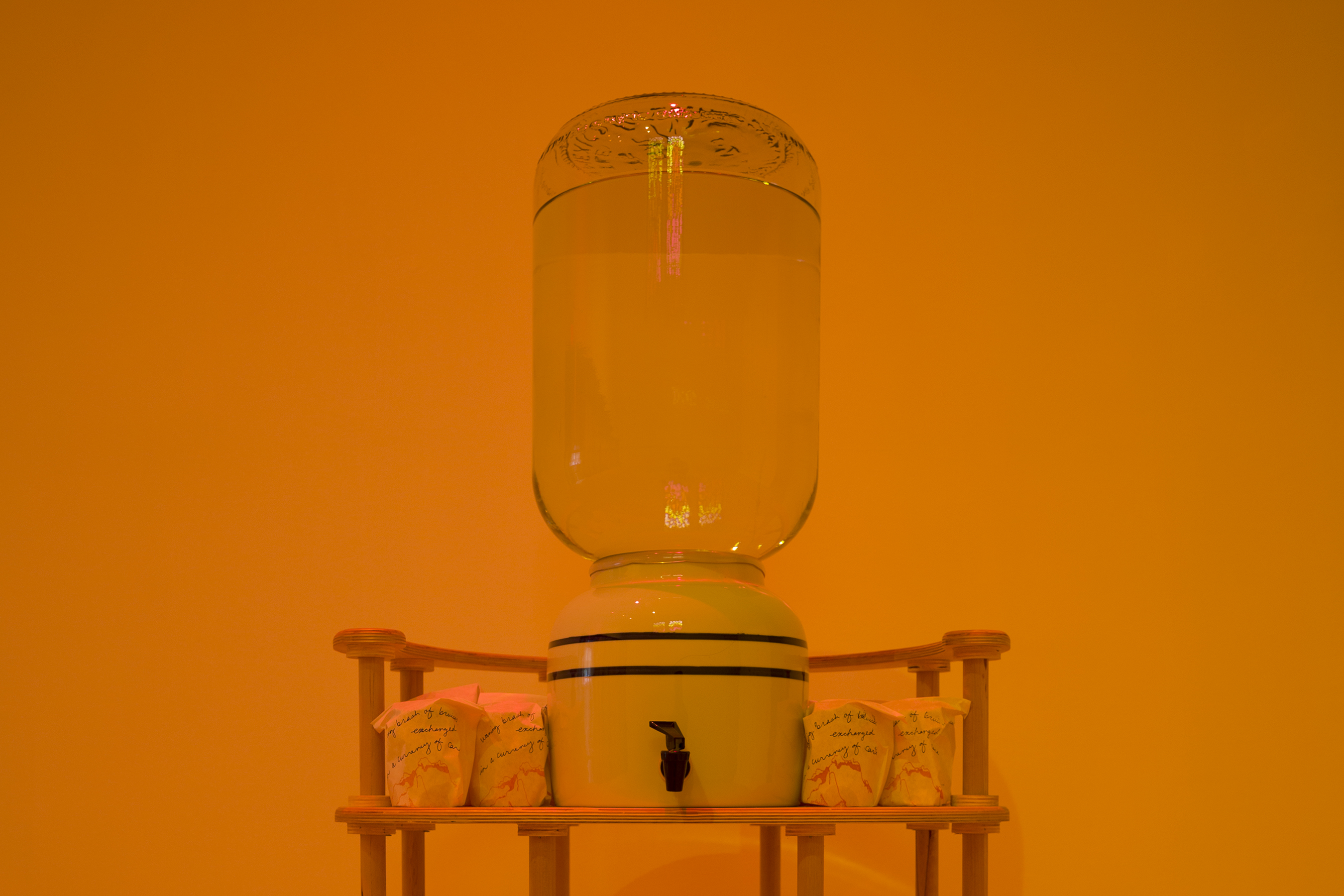

If we’re to take as the subject (or maybe it’s better to say the substance) of this exhibition to be light, then it stood to reason that we must open up the gallery to as much light as we could. That meant we needed to cut loose the bound in window, restoring the pair of windows that hadn’t been in the gallery since 1985. Where the windows themselves are time capsules of Western Front’s architectural transformation over the decades, Westman’s two cuculorises function similarly across temporal distances. The patterns cut into fir plywood are not random patterns, rather they’re traced directly from tree shadows in Vancouver. Scribed from light passing through trees, these cuculorises cast the shadow of something that might have been here before this building was here.

In all of this, I come back to the question: is light even a substance? Scientifically, it sits somewhere in between wave and particle, exhibiting properties of both. We can’t hold it, but we can feel it, though how we feel it is more closely related to its properties as wave (heat) rather than as particle (mass). As a wave it travels across distances, collapsing space with its speed. It permeates, streams in through windows, blurring the boundaries between inside and outside. Though light has qualities that we associate with land—prairie light, northwest coast light, mountain light—it is less bound in by the carving up of land into property. What are the implications in considering light as both intrinsically tied to place, but also persistently obfuscating the territorial boundaries that complicate our relationship to place. Westman’s work in this exhibition—film, photographs, and sculptures—all consider this duality of light as a thing that is not a thing, both material and immaterial. Here, light passes through, it permeates, it reflects, it is felt, but will always resist any attempts at holding onto it.

EXHIBITION TEXT: Pablo de Ocampo

CURATED BY: Pablo de Ocampo for Western Front Gallery

MAY, 2019

REVIEWS:

Nicole Kelly Westman- Reviews- Western Front, for Canadian Art by April Thompson

Nicole Kelly Westman at Western Front, Vancouver - Reviews - for Akimbo by Justina Bohach